311. Pensacola's Yellow Fever Epidemic 1905

- Author

- Feb 28, 2020

- 36 min read

In August 1905, a three-masted sailing ship nosed its way into Pensacola Bay and dropped anchor just off Palafox Wharf and waited to unload its Caribbean cargo. But unfortunately, it also carried a cargo of mosquito larvae carrying the dreaded Yellow Fever, which was inadvertently brought to Pensacola from their last port of call. If one of the ship’s sailors was already infected surely the captain of the culprit vessel would have been unawares or he would not have put into port. Every captain of every ship was aware of the procedure for handling any suspected yellow fever situation. It was marine law that the captain must inform the harbor pilot of any disease or medical situation as soon as he stepped aboard to steer the ship into port. The pilot would then immediately alert the Pensacola health officer Obed M. Pryor so that the situation could be investigated, and appropriate action taken.

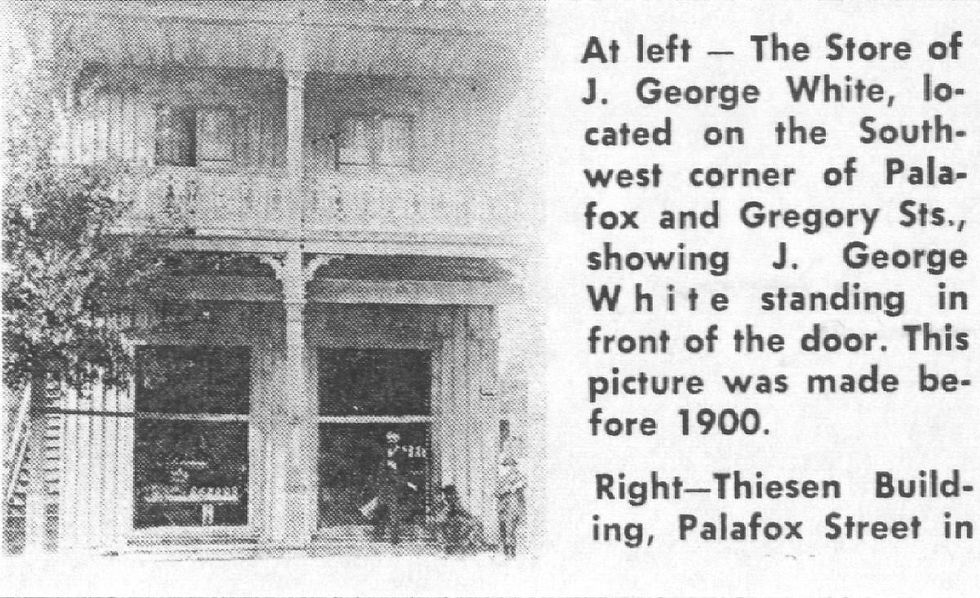

Pryor was the chairman of the city’s “Harbor & Sanitary Board” and had a staff of two other members to assist him. His group came under the direction of the Pensacola Board of Health, which was comprised of himself plus Mayor Thomas Emmet Welles, John George White Sr. (Photo #1), Oscar E. Maura, William R. Meriweather, and Alex Zelius. Depending on Pryor’s investigative findings a report would immediately be made to the city physician Dr. Juriah Harris Pierpont. (Photo #2)

These men were some of the most influential citizens in the city and in today’s society would be thought of as the communities “movers and shakers.” For example, Mayor Welles was a partner in the E. E. Saunders Fish Company, the Jacoby Grocery Company, President of the Gulf of Mexico Railway Company, and was vice president of the Citizens & Peoples Bank. Oscar E. Maura was a local merchandise broker while William R. Meriweather was a Pensacola money broker.

If the diagnosis proved to be Yellow Fever, then it was these men that had the connections to quickly mobilize enough forces to move against it. Of course, if there was any possibility of infection, the offending ship would be directed to the quarantine station on Santa Rosa Island where it would be forced to anchor for a period of twenty-one days. If need be the port officials would require the ship’s captain and crew to burn sulfur spread out over their ballast rocks to hopefully kill any of the disease carrying mosquitoes and their larvae. However, in this case no ship was quarantined because none of this information was available at the time of the first victim’s discovery.

Another explanation of how the disease reached Pensacola was an innocent mid-summer trip to visit family members in Louisiana. The deadly drama began on July 15, 1905 when several hundred citizens of Pensacola boarded an excursion train bound for New Orleans to visit their relatives and see the sights of the huge port city. Unfortunately, the very area they were visiting had become infected with Yellow Fever from mosquitoes brought in by the Caribbean ships to the wharves of New Orleans. However, the incubation period of the disease discounts some parts of this theory unless the patients were in the advanced stages of the disease at the time they arrived back in Pensacola.

The disease called “Yellow Fever” or the slang “Yellow Jack” is a virus carried by a certain Caribbean mosquito that can be transported by sea going vessels through its larvae. This is the reason that the disease usually entered the United States through its Gulf of Mexico ports of call. The virus remains silent in the body during an incubation period of three to six days before it enters one of two phases. While some infections have no symptoms whatsoever, the first one known as the "acute" phase is normally characterized by fever, muscle pain, a prominent backache, headache, shivers, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting. Oddly enough the high fever is associated with a slow pulse. After three to four days most patients improved, and their symptoms disappear.

However, about 15% of the infected patients then entered a "toxic phase" within twenty-four (24) hours. Their fever reappeared and several body systems began to show further symptoms. The patients rapidly developed jaundice (thus the name Yellow Fever) and complained of abdominal pain followed by vomiting. Bleeding occurred from the mouth, nose, eyes, and stomach. Once this happened, blood began appearing in the vomit and feces. Kidney functions began to deteriorate, which led to complete kidney failure with absolutely no urine production. Half of the patients in the "toxic phase" died within ten to fourteen days. The remainder recovered without significant organ damage.

Yellow fever was difficult to recognize, especially during the early stages. It could easily be confused with symptoms of malaria, typhoid, the hemorrhagic viral fevers, dengue fever, leptospirosis, viral hepatitis and poisoning. Today a laboratory analysis would be required to confirm a suspected case, a method unavailable in Pensacola in 1905.

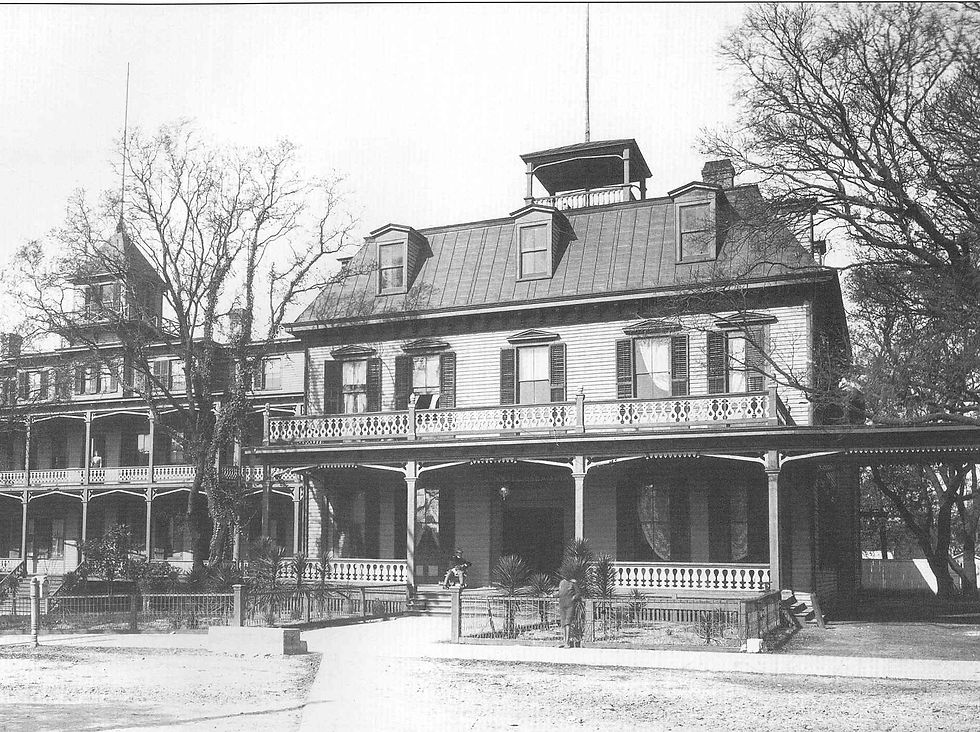

By whatever method of entry into Pensacola the first cases began to appear as early as July 31st when a 45-year old clerk by the name of H. D. Brooke, came down with the first symptoms. He was living at the Plaza Hotel (Photo #3 as seen in the 1920’s) at the time, which was located on the corner of Jefferson and East Government Street. The condition of the man worsened with time and he finally died on the 12th of August. His body was hastily buried in an unmarked grave in St. Johns Cemetery.

Unfortunately, this was the port authority's first indication that the dreaded disease had begun to work its way east from New Orleans, which had already experienced an outbreak of its own. Brooke’s proximity to the waterfront made his death a prime suspect for a diagnosis of Yellow Fever.

By August 30th, several more cases began to appear when three Greek immigrants by the names of Manuel Migul, George Klonio, and Chris Thimoras became ill. Ironically all three men had been on the excursion train from Pensacola to New Orleans on July 15th thus adding to the original theory of the disease’s origin. Migul lived behind his fruit shop at 144 East Government Street and the other two lived close by. From an investigative standpoint this placed the first four victims in the first block of East Government Street.

Four cases by themselves did not constitute an epidemic but everyone in town had read the newspaper accounts where Yellow Fever had already struck hard at Natchez, New Orleans, Memphis, and Gulfport and it now seemed to be spreading eastwards. Every day the papers carried numerous stories of the death toll mounting in these other cities. By August 31st, a man by the name of William J. Abell was stricken with the symptoms and an investigation led to the fact that he lived close to the three previous Greek victims. He was a tailor who was employed as the manager of the Pensacola Pressing Club and boarded at the Plaza Hotel on East Government Street where the first victim H. D. Brooke had also lived. Unfortunately, Mr. Abell shared the same fate as Brooke and died on September 1, 1905.

At least now the health officials had a target area for their investigation before the disease got too far out of hand. In the meantime, another citizen by the name of George Dansby reported to the hospital on September 2nd with high fever and vomiting. Even though Dansby lived at 20 East Brainard Street, which was far outside the original target area, the authorities knew that he was employed in the downtown area and could easily have caught the virus there.

The next day Francis C. Brent, Pensacola’s most influential financier and a Confederate veteran, was notified that his 20-year old son George Shuttleworth Brent (Photo #4) had fallen ill at their downtown home at 108 East Romana Street. This was quickly followed by five more victims on the 5th of September, one of which was Brent’s 15-year old daughter Genevieve. The rest were identified as John Garcia, John Humphreys, Mrs. C. P. Ketierer, and 26-year old Charles P. Winters who all lived downtown close to one another. Charlie Winters was a likable young bartender that was boarding at the Escambia Hotel (Photo #5) on the corner of Palafox and Wright Street at the time he noticed some of the first symptoms.

That very day a long line of infected patients began to die. The first was Charles Winters whose body was quickly transported to the St. Joseph’s Cemetery at today’s Pace and Jackson Street and buried with little ceremony. As quickly as the funeral arrangements were made for the first of the dead, other Pensacolians were collapsing and being rushed to the already overcrowded St. Anthony’s hospital (Photo #6). Previously called the Pensacola Infirmary in 1900, the hospital had moved just north of the business district to 104 West Garden Street and renamed St. Anthony’s.

By this time it was very apparent that most of the dead and dying came from the Intendencia, Devilliers, and Spring Street area, all close to the waterfront, which gave credence to the theory that the disease had been brought here by one of the ships anchored in the harbor.

The ever-lengthening list of those that collapsed now included Fritz Housebotter, Horace Rosique, and Judge Boykin Jones (Photo #7). Judge Jones would survive the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1905 and return to work at his downtown business “B. Jones & Company.” He was already a well-known figure in Pensacola during those days in a variety of areas. He was born in Columbus, Georgia on February 15, 1840 and at the time of the Civil War he was attending medical school at the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. When his home state of Georgia seceded from the Union, he left New York on the next train for home. He enlisted on April 16, 1861 as a private in the “Old Columbus Guards,” which was attached to the 2nd Georgia Infantry Regiment. As history would have it, he was one of the soldiers selected to make up the personal bodyguard of Confederate President Jefferson Davis at the time of his inaugural ceremony in Montgomery. He served the “Lost Cause” for four years and ten days until he was paroled on April 26, 1865 in Columbus, Georgia with the remnant of his command.

After the war Jones tried to make a living as a farmer planting cotton in Russell County, Alabama before he moved on to Pensacola in 1881. Here he served the community as a judge, coroner, and local businessman. From 1913 until his death he served as post commander of Ward Camp #10 of the United Confederate Veterans in Pensacola. Sadly, his wife passed away in January 1906 leaving him alone for the next decade and a half. Several months before his own death he moved into the home of his daughter Lizzie and his son-in-law Richard Abercrombie Hyer at 704 North Palafox Street. By this time, he had become ill and feeble due to the infirmities of his advanced years. On Monday morning of April 2, 1923 around 10:05 AM the old Confederate breathed his last and silently slipped into the pale nations at the age of 83-years old. His funeral services were held in the First Methodist Church officiated by his pastor Reverend John W. Frazier. His son William Chipley Jones made all the arrangements and every member of the United Confederate Veteran organization in Pensacola attended the funeral. At the time of his death he was one of only three surviving members of President Jeff Davis’ old bodyguard. He and his wife are now both at peace, lying together in St. Johns Cemetery in section #17.

Now there was no doubt in the minds of the city’s health officials that there was a full-fledged Yellow Fever epidemic in the making in Pensacola. They responded immediately and began a house to house search for more victims as they tried to pinpoint the origin of the infestation. Residents were told to rid themselves of any outside containers of water that may serve as a breeding ground for the mosquitoes while inspectors fumigated 165 houses in the cordoned off district. They even went so far as to place barrels of burning sulfur at all the strategically located street corners. This caused a smelly and dense yellow pall of smoke to hang over the city that choked the Pensacolians but had little effect on the spread of the disease. Several inhabitants of the area were even taken into custody by the police for failing to abide by the city’s instructions to clean up their property.

Then Herman Pinney, a telegraph operator for the Western Union Company, fell seriously ill. He was the son of Samuel Leo Pinney and nephew of Jonathon L. Pinney both former Confederate cavalryman with the 6th Alabama Cavalry Regiment. He lived at 207 North Reus Street with his widowed mother Clara whose own brothers had fought for the Confederacy as well. His home was outside the area of infection, which created a panic that the epidemic might be spreading outside of its original downtown zone. However, they once again noted that during the day Herman worked downtown at the Western Union station so was probably infected there rather than his home. Pinney would survive his close brush with death and begin working as an operator for the Postal Tel-Cable Company in 1908 while he boarded with his brother Henry C. Pinney at 218 North Devilliers Street.

Not knowing the origin of the disease produced a quandary for the public health officials. While they were trying to eradicate the infected Caribbean mosquitoes in the downtown area they didn’t know if other ships sailing into port may be carrying more larvae to take their place. To remove this possibility the officials decided to quarantine the harbor from any further shipping activity until all incoming ships could be inspected. To this end the coast guard provided a patrol boat to assist in enforcing the mandatory quarantine. The cutter “Penrose” plus two other launches were made available to the city for patrolling the local waters twenty-four hours a day.

They also decided to set up a quarantine camp in the community of McDavid, located north of Pensacola, to house any person interested in leaving town. These refugees were required to remain in the encampment surrounded by barbwire for a period of seven days, which was the suspected incubation period for the disease. If they exhibited no symptoms at the end of that time, then they were free to continue their journey. The city was taking no chances in allowing the disease to spread throughout the surrounding countryside. (Photo #8)

But by September 9th ten new cases were reported to the health officials along with the death of police officer William Fisher who had fallen ill four days earlier. Officer Fisher had traveled each day from his house at 212 North Devilliers Street to the downtown police station located within the quarantine area where he was most likely infected. Dr. Whiting Hargis did all he could for his law enforcement patient, but all his efforts were in vain. His body was turned over to the undertaker John G. Wood who buried him in a hastily dug grave in St. John Cemetery where his marker has long since disappeared. The next victim was the vice consul from Norway, Mr. Olaf Rye Wulsberg, who died on the 11th along with Michael Christman of 116½ South Tarragona Street proving that no matter what station in life you occupied in society you were not immune from the perils of “yellow jack.” The 56-year old Wulsberg was buried alone in St. Johns Cemetery forcing his family to return to Norway to continue with their lives.

As the disease spread and panic among the populace began to heighten, the citizens in the outlying areas began to take their own precautionary measures. As far away as Cottage Hill the word was put out that anyone from Pensacola was not welcomed in their community. Notices were posted all over the place that anyone from the city that tried to disembark from the train or the riverboats at Cottage Hill would be subject to arrest and detainment.

In the meantime, the fever in Pensacola was continuing to strike the citizens on the south side of the city much harder than any other district probably because of the poor sanitary conditions that existed there. Because of this situation some of the residents attempted to flee by eluding the quarantine patrols established by deputies who ringed the city with roadblocks. Deputized volunteers also patrolled along the railroad tracks and depots leading to and from the city should any citizen attempt to escape in that direction.

On September 13th seven new cases were added to the list one of which was 21-year old Ralph Berlin of 108 W. Chase Street. Ralph was the son of Jake Berlin one of the local timber inspectors for the Henry Baars Company. He was also a member of the Berlin family that would soon open several popular men’s clothier stores on South Palafox a few decades later. But by this time everyone was on the verge of panic and the city officials were having to take more drastic measures to keep any of the infected citizens within the city limits. One of the areas they had to secure was the L&N railroad tracks into and out of Pensacola. To this end they sat up a sentry post at the Goulding station just north of town near today’s intersection of Cross and Palafox Street.

One of the men they recruited to assist in the coordination of this security post on September 14, 1905 was Francis Ross Goulding or “Frank” to his family and friends. He was a 63-year old veteran of the Confederate army where he served with Company “F” of the Jefferson Davis Legion from Georgia. That night he had told his wife Sarah Ann that he would be back late so not to wait up. Around 7:00 PM he was standing on the track looking down the rails with his back to a waiting train when the engineer began backing it up. He obviously had no way of knowing that Goulding was still standing in the middle of the tracks behind him. He struck the old Confederate knocking him to the ground and before Goulding could roll off the track out of harm’s way the train’s wheels ran over him mutilating his poor body beyond repair. The tortured man lingered on for a short while before he gave up his spirit and joined the fate that he had so perilously escaped during the war. Everyone was shocked beyond belief and no one knew what to do. He was so crushed and torn that no one could do anything for him to relieve his pain and suffering before he died. What they did do was to order a special train to bear his body to the home of his son at 800 North 6th Avenue located near the intersection of 6th and Cervantes Street. Fortunately, Frank died of his massive injuries before the train pulled into Pensacola. Upon arrival they off loaded the body at the Union depot at Tarragona and Wright Street with as much tenderness as they could offer the old man and loaded it onto a commandeered wagon. His family had been forewarned that he was seriously injured but were not aware of his death until his body arrived at their home. Goulding was quickly buried with what military honors they could muster within the time limitations in St. John’s Cemetery in section #11. His body was laid to rest accompanied by his comrades from Ward Camp #10 of the United Confederate Veterans in Pensacola. Frank’s wife Sarah would apply for his Confederate veteran’s pension the next year and would receive $300.00 per year until she joined him in death in 1929.

Six days later, on September 20th Jonathon Q. P. Ellis died at his house at 114 North Alcaniz Street at the age of 40-years old and was buried in St. Michael’s. He was a railroad machinist by trade and had been working under the supervision of his foreman Lee Brine at the time he was stricken.

By the 24th James A. Perdue of 416 East Wright Street died which added to the death toll already mounting. Perdue was a workman for the L&N shop downtown and had been a clerk for a grocer by the name of John A. Van Pelt, the brother of the sheriff. Dr. William C. Dewberry (Photo #9) pronounced him dead and sent his body to Frank Pou’s for burial in St. Joseph’s Cemetery. Today his grave is no longer listed among the deceased in that cemetery.

In addition to his death nine more cases were reported having come down with the preliminary symptoms. The next day on September 25th twenty-five more cases were added to the list. By this time, whole families living in the same household were being stricken with the disease. That same day saw the death of a 39-year old German by the name of Karl F. Haas who rented a room at 217 E. Government Street and worked for a while as a piano tuner for the Clutter Music House (Photo #10) and then the Jesse French Company. Joining Mr. Haas was one of the city’s poor, 39-year old Ms. Jane F. Wilson who lived at 222 East Intendencia Street with Mrs. Ernestine R. Burgoyne. Ernestine was a widow following the death of her husband George R. Burgoyne at which time she moved in with Ms. Wilson to help with their living expenses. Ms. Wilson was a stenographer for the Avery & Avery Hardware Company (Photo #11) and was also a notary on the side. Their combined income was enough to keep a shelter over their head and enough food on the table. Ernestine helped nurse her friend and housemate until old yellow jack finally claimed her for his prize on the same day as Haas. Her body was borne to Potter’s Field where the poor and indigent were interred with little pomp and circumstance.

Three days later, on the 28th three more victims joined their comrades in death. The first was a 17-year old colored boy by the name of Jackson Daniel who was boarding at 411 East Strong Street. He was working as a common laborer when he was struck down in death by the virus in mid-September. The same day saw the death of Will Stanes, a 48-year old colored man and James C. Rice both of which lived at 810 West Jackson Street. Although both lived a long way from the city, Jackson was working downtown as a “hackman,” which in those days was the equivalent of a taxi driver while his housemate Rice was a teacher at a colored school in town. After their demise Jackson was buried at St. John’s while Stanes was interred at Magnolia, a colored cemetery on “A” Street two blocks north of Cervantes.

The 29th of September was the worst death toll suffered by the port city since the outbreak of the epidemic. Four Pensacolians succumbed to the virus within hours of each other. First of the victims was a white male of unknown age named Daniel Agan who died at his home at 605 South Palafox Street and was buried in an unmarked grave at St. Joseph’s. He was joined there by 15-year old Johannes Braeker who was serving as a tailor aboard the German commercial ship “The Kaiser” anchored in Pensacola Bay. Almost all foreign seamen went to St. Joseph’s Catholic Cemetery, which was laid out around 1900 by the first pastor of St. Joseph’s Church, Reverend Robert Fullerton (Photo #12). The name originated from a group at St. Michael’s called the “St. Joseph’s Colored Society” who split off and opened their own place of worship. Compassionately Fullerton agreed to bury foreign sailors in their cemetery as well as the commemoration of any sailor who had died at sea. There are two monuments in the cemetery dedicated to over 184 seamen who are buried there. So naturally when young Braeker died from the fever there was no question as to where he would be laid to rest. Both men were quickly followed by a 30-year old colored cook living at 224 East Intendencia Street by the name of Laura Albritton who in turn was followed by the fourth victim of the day, Mr. Anthony Martin who passed away in St. Anthony’s Hospital. He was only a poor gardener and there was no money for his funeral, so he was carried up to the “Poor Farm” and buried in Potter’s Field.

The Poor Farm was first established in March of 1885 with John Edward Bowman (Photo #13) appointed as their first “keeper.” There were four buildings for the indigent citizens as well as the keeper’s home and office. The entire institution was spread out over ten acres with another ten under cultivation. Adjacent to the poor farm was the cemetery where paupers were buried when they could not afford a plot in one of the regular cemeteries or had no money for a funeral. And during this epidemic there were more than enough customers vying for the space. John was born on September 18, 1850 and would pass away on September 18, 1931 after serving the county farm for forty-one years as well as the postmaster and a merchant in McDavid. The next day another victim was added to the list when a carpenter named William T. King died in his room at 120½ East Government Street and was quickly carted off to St. Johns by the death wagon.

Now things were getting out of hand and the county officials ordered their eradication teams to go to the house of each victim and pour carbolic acid in a moat dug around the house in hopes of killing any of the mosquitoes. However, their preventive measures such as spraying (Photo #14) were proving futile while new cases were coming in faster than they could hope to treat them.

The officials noticed at this time that the disease was spreading out of the downtown area and into the west side of Palafox Street and to the north of Wright Street. On the 2nd of October 53-year old Dr. Henry H. Boulter from Canada began to rapidly weaken and his condition became critical. Boulter was a local dentist whose office was located on the southwest corner of Palafox and Intendencia Street. He was living alone at 313 North Spring Street when he was struck down by the disease. Dr. William A. J. Pollock (Photo #15) did what he could but the dentist finally succumbed that evening and was buried in an unmarked grave at St. John’s cemetery. His death brought the death toll to date to thirty-one (31) with the number of cases discharged at sixty-three (63) and the patients under treatment to eighty-one (81). With nine new cases being brought in and added to the list, the disease had now begun to reach epidemic proportions.

With the beginning of October everyone was praying for an early cold spell to kill off the infectious mosquitoes, but the weather remained mild and the victims kept coming. On the 3rd of October they lost three more when a 20-year old carpenter named Eddie Beladeau died in his bed at St. Anthony’s Hospital and was buried in haste at the Poor Farm. The next victim for the day was one of the first children to succumb and this time the banshee picked the ten-day old infant of the local blacksmith Louis F. Joh at their home at 214 S. Alcaniz Street. The last of the day was a shipmate of the young Johannes Braeker off the Kaiser. The 26-year old Second Mate G. Frederick Menge joined his young friend at St. Joseph’s that same afternoon.

It seemed like every day Pensacolians were dropping like flies. The doctors were exhausted, and the gravediggers could hardly throw another shovel full of dirt over their shoulder. Markers could not be made fast enough therefore many of the victims were given wooden crosses that quickly rotted away within a few years in the humid southern climate. On October 4th a 33-year old colored porter, Henry Wright, died at his East Romana Street home and was buried at Zion followed by five more deaths the next day. On that fateful day of the 5th of October 38-year old Fenandor G. Debroux gave in to the dehydration of the high fevers and vomiting at his home and grocery at 427 East Gregory Street. He was pronounced dead and carried from his 10th Avenue and Gregory Street home straight to St. Johns Cemetery. A third sailor from the Kaiser joined his two shipmates at St. Joseph’s after dying aboard ship. Tragedy struck the ship yet again when 20-year old Richard W. Heine Dulz was laid to rest with his comrades and the appropriate letters of notification were sent to his family in Germany. (Photo #16 are the graves of all three sailors from the Kaiser-Dulz in foreground, Braeker upper left, and Menge upper right) But the grim reaper was not quite through with his victims this day. James E. Hyde, 37-years old, died at his home on Tarragona Street and the dead carpenter was carried by wagon to the Poor Farm cemetery. While the wagon bearing his pitiful remains was heading north another was plodding its way toward St. Johns to bury a 20-year old Norwegian sailor named Jonathon Kelly who had died in St. Anthony’s Hospital. That same wagon carried a second coffin with another victim from New England by the name of Julia Schults(z). The 69-year old woman had died in her room at 108½ East Government Street from the viral complications while her 64-year old husband Frederick O. lay on his death bed himself at St. Anthony’s Hospital. The old watchman joined his wife at St. John’s two days later.

Pensacola lost one of its favorite Greek citizens on October 6th by the name of Tony Corfetti who was the manager of Pensacola’s gathering place for the rich and powerful called “Constantine Apostle’s Restaurant” located on Government Street. Mr. Apostle was the first Greek immigrant to settle in Pensacola in 1865 at the end of the Civil War. His original name was Constantine Apostolou Panagiotou but later changed it to just “Apostle.” The Apostle’s were also related to the Liollio’s who opened a well-known steak house restaurant in Pensacola several decades later. With Constantine came his brothers Nick and George Apostle who found the business life of Pensacola much to their liking. He later returned to his homeland on the island of Skopelos in 1893 to collect his nephews in the Liollio family and return to the city of opportunity on the quiet Gulf Shore. Constantine died himself on September 4, 1909 in the Pensacola Sanatorium from Bright’s disease and was buried in St. Michael’s.

Over the next two days two more deaths were logged in by the overworked coroners. Isom Basil Bogart, 19-years old, died at his home at 762 E. Wright Street on the 8th followed on the 9th by the death of one-year old Annie Loraine Edmonson on Clubbs Street. Bogart’s wagon headed for St. Johns while Annie’s went toward St. Michael’s. The 10th brought three more deaths in rapid succession. The first was 37-year old Frank L. Barien who died in his room at the Hotel Southern at 28 East Garden Street. He was the proprietor of the hotel but unfortunately the yellow jack moved his permanent residence to St. Michael’s Cemetery.

The 10th also saw the demise of the British vice consul, Frederick R. Bonar who died at the age of 32-years old in his bed at 27 West Gregory Street and was buried in St. John’s in section #56. His wife Florence would succumb thirty-six days later. Along with the British consul, the 54-year old Norwegian Harbor Master, William Olsen died at his home at 416 West Government Street bringing the death toll to forty-five victims. Olsen had lost his wife to other causes only a few months earlier and was trying to raise their three children without her. Unfortunately, he was a large obese man, which added to the complications created by the disease and proved fatal to him in the long run. He was buried in St. Michael’s cemetery.

The next day was no different as the wagons lined up for their daily haul to the entrance gate of the pale nations. Fortunately, this day only required one wagon for 59-year old Nannie A. Wilkerson, a dressmaker, who had died at her home and office at 523 DeLeon Street. That same wagon would later carry her merchant husband John W. Wilkerson to lie beside her in St. Johns at the age of 61-years old. The couple had migrated to Pensacola from Coffee County, Alabama and now lay together in peace in section #16 of the old graveyard.

On the 12th of October an older missionary woman by the name of Margaret Gibson died in her hospital bed where she had been taken at the time she was stricken. She normally kept a cheap room at 519 Guillemard Street because missionary work was supposed to come from the heart and not for the wallet. Her lifestyle of poverty earned her a burial site at the Escambia County Poor Farm but hopefully her heavenly residence was a much nicer place. The 13th saw three more deaths added to the list. They were those of 73-year old George C. Hardy who was a former Army officer with the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment who died at 308 South Alcaniz Street while living with Captain Lars Andersen, (Photo #17) a local harbor pilot. Andersen saw to it that his old friend was buried properly in St. Johns, a location destined for Lars and his family several years later. Lars would pass away himself on April 14, 1932 and sadly would precede his son Leo by only seven months. On November 5, 1932 Leo joined his father when he was killed in an automobile accident on today’s Highway 98 at the Lillian Bridge on his way back from a trip to Mobile. Both are buried in St. John’s cemetery.

The second of the day was 73-year old James I. Stephens who was a local jeweler and optician working out of his home at 120 South Palafox Street. He died in his own bed and was transported by his loving family to St. Michael’s for burial. The last of the day was 30-year old Nicholas Triantafilo who died aboard a Greek merchant ship anchored in the bay off Muscogee Wharf.

The situation had become so bad that normal burials were suspended, and the bodies were carted away in wagons (Photo #18) in the early morning or at night and placed in shrouds in hastily dug graves in St. Michael’s and St. Johns Cemeteries. There were no funeral services allowed and those without burial plots were placed in a common grave with the others at the corner of the graveyard. Mournfully there were few markers placed on their graves to note their passing into the pale nations. The situation deteriorated to the point that Dr. William Crawford Gorgas wrote years later that he had been a doctor, undertaker, clergyman, and gravedigger all at the same time.

But no matter how hard the doctors and nurses worked around the clock the list of the victims kept getting longer and longer. On the 14th a middle-aged merchant by the name of William Cross succumbed to the yellow jack at his home at 528 East Gregory Street and was buried in St. Johns Cemetery.

The next morning added four more names to the list. First there was a little five-year-old girl named Fabie Amos who was the daughter of Hugh S. and Mary L. Amos. They were renting a room at 400 North Hayne Street while her father was employed as a yard master and her mother was working as a teacher. As the two parents watched helplessly their daughter slipped into a coma then shortly afterwards into death. They lovingly buried her frail little remains in St. Johns Cemetery where she still rests today. The second of the day was 21-year old Henry Jackson who was a colored laborer living on West Zarragossa Street. He was quickly buried in the Zion Cemetery as the bodies continued to pile up and overwhelm the gravediggers. The third victim was a poor colored woman by the name of Annie Bell Stevens that died in a makeshift hospital at Russell’s Hall at #5 North Tarragona Street. Since her family had no money to bury her, she was transported by wagon to the Poor Farm and interred among the other indigent victims. The last of the day for the 15th was 32-year old Sideri Stilava who had been stricken with the fever aboard his Greek merchant ship and taken to St. Anthony’s Hospital where he died. He too joined Annie Bell at the Poor Farm.

The panic among the citizens had reached such a level that all public gatherings of any kind had been suspended and the streets of Pensacola looked like the avenues of a ghost town. Since most incoming ships were now being quarantined there was absolutely no activity on the waterfront and even the streetcar companies had suspended all their trolley runs past 8:00 PM.

The citizens had absolutely no idea when the nightmare was ever going to end. Day in and day out the corpses piled up while the weather remained mild enough for the mosquitoes to breed and flourish. On the 16th one of the piano representatives, W. A. Walls, from the “Jesse French Piano Company” (Photo #19) finally succumbed to the disease joining a co-worker Karl Haas who had been one of the first victims to fall. The manager of the store was Willis W. Walls who had lost two employees in a matter of weeks because of the wicked disease. The second for the day was a little nine-year old colored girl by the name of Ethel Sellars who died in her bedroom at 212 East Gregory Street and was buried with Mr. Walls. The next morning was more of the same with a 45-year old Norwegian Theo Signe Eitzen dying in his home at 416 East Wright Street and was buried that same afternoon at St. Johns. The second burial on that day was at St. Michael’s cemetery after 12-year old George A. Byrnes died that afternoon in the home of his family at 318 East Intendencia Street. He was living with his widowed mother Mrs. Mary F. Byrnes and his siblings Florence and Michael J. Jr. who helped support his family as a collector for the Pensacola Loan Company. George was laid to rest next to his father Michael J. Sr. who had preceded his son in death.

The next day the Touart family contributed their own representative to the list of dead on the 18th of October. The Touart’s were an old established Pensacola family that occupied most of the homes around the intersection of Florida Blanca and East Intendencia Street. As the morning sun rose above the horizon 19-year Charlie Touart breathed his last and slipped into eternal oblivion in his home at 401 East Intendencia Street. He was living with his brother Gomes Touart who was employed as a screwman and his widowed mother Josephine Stinson Touart. Charles and Gomes were the grandsons of Francis “Frank” B. Touart who had served with the Confederacy during the war. His grandfather had been shot through the hip while carrying the regimental flag for the 1st Florida Infantry Regiment at the battle of Perryville. Charles himself had been working as a bayman at the time of the epidemic and had no choice but to continue going to work each day and putting himself in peril in order to help with the family expenses. However, much to his dismay the area along the waterfront was one of the greatest concentrations of the disease carrying insects.

To educate the public the newspaper published several articles on “The Transmission of Yellow Fever and How to Nurse it,” which only served to heighten everyone’s already exaggerated fears. As soon as the papers reached the Ferry Pass community, the Majors’ clan made sure they avoided any trip to town until the crisis had passed with the first frost of fall. They all agreed that their vegetables, chickens, and eggs would be sold to the people in the outlying areas rather than taken to the downtown markets until the situation improved.

One of the first published advertisements in the newspaper was for “Bosso’s Blessing.” It was produced by Constantine Apostle who was living at 300 East Romana Street in 1896 and was the first Greek to settle in Pensacola. The advertisement in 1905 read, (Photo #20 is another advertisement) “Don’t Fear Yellow Fever! There is very little danger of yellow fever coming to Pensacola but even if it did, our people need not fear it. BOSSO’S GREAT REMEDY will positively cure yellow fever and, better than that, if you take a bottle of Bosso, it will be impossible for you to take the fever. No fever of any kind can exist if you take Bosso! For sale wholesale and retail by Constantine Apostle at 216 South Palafox Street.”

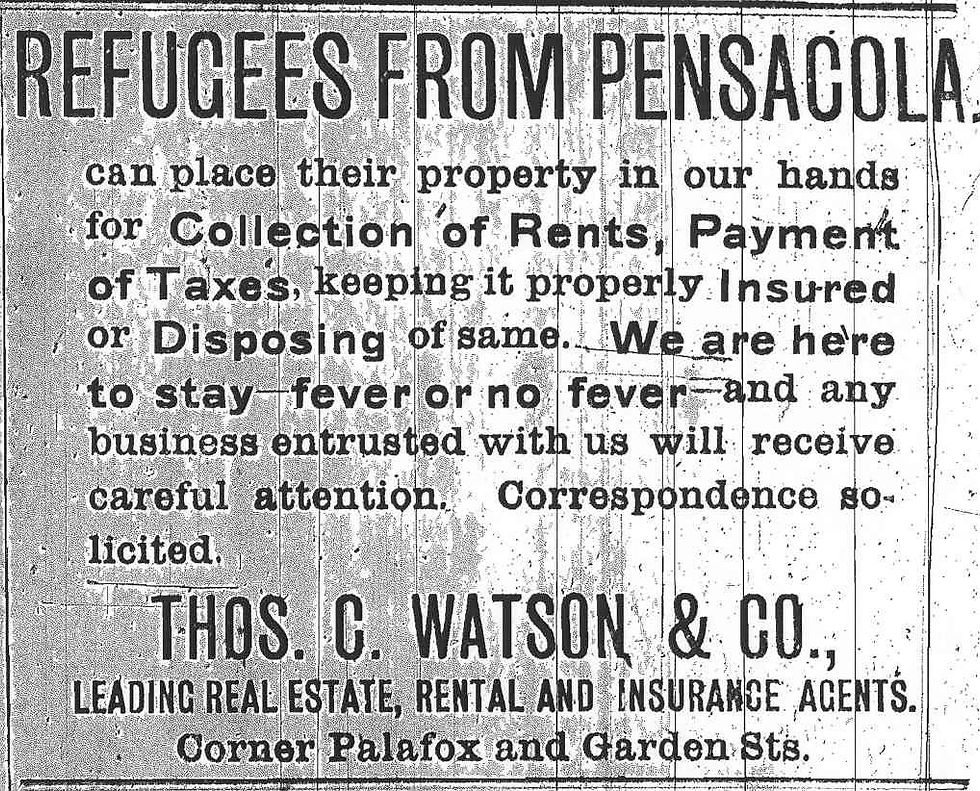

Other advertisements (Photo #21) were submitted by Pensacola businessmen such as Thomas C. Watson in hopes of securing real estate placed in hands for safe keeping while the town’s citizens fled the area.

On the 11th of October a 22-year old James H. Cox, originally from England, was working at his job on the city wharf downtown when an infected mosquito bit him. Within 24-hours he was close to collapse from the symptoms of the disease and by the 19th had succumbed from the virus at his home on East Zarragossa Street. Sadly, if he had only had a little bottle of “Bosso’s” he probably would still be with us today. On the 20th a small infant named Andrew Geiger died at his parent’s home at 710 West Gregory Street and was buried in St. Johns. His father was employed as a tailor for Manuel Solomon but after the child’s death the parents moved on with their life and were buried elsewhere years later. Two days later another child was claimed when seven-year old James William Steel, the son of William and Marie Steel, fell victim to yellow jack. The boy’s father was a watchmaker and had sat with his wife next to their son’s bed for a week as his condition grew worse every day. Finally, on the morning of the 22nd the boy died in his bed at their home at 121 North “A” Street. His parents dutifully escorted the funeral wagon to St. Michael’s for the burial services of their young son. His two-year-old brother Charles B. Steel would survive the epidemic and would not join his older brother until September 30, 1944.

The next day three more joined the others in the pale nations when 51-year old James H. Caswell died at a relative’s house on Olivia Street. He normally lived on Little Bayou (Bayou Chico today) and worked as a laborer for the Brent Lumber Company at their island sawmill. His family was dirt poor and could not afford a funeral, so he was shipped to the Poor Farm for burial.

Ironically, Brent Island no longer exists today but at one time it was located just off the mouth of Bayou Chico. However, the erosion from the hurricanes of 1906, 1916, and 1926 caused the island as well as the remains of the old sawmill to disappear below the waves forever.

The second death of the day was a 29-year old Greek boy by the name of Angelo Coropos (Photo #22) who died at his home on the corner of Guillemard and Belmont Street. Angelo owned his own fruit stand that he set up every morning at 201 West Intendencia Street. He was carried to St. John’s Cemetery in the same wagon that also carried the third victim of the day. After dropping Angelo off next to the pile of freshly dug earth the wagon continued to St. Joseph’s with the body of 35-year old Harry A. Olsen, a fisherman who had died that morning at his house on West Main Street. The next day was no better and as the sun rose 22-year old Mrs. Mary M. Gunn breathed her last at her home at 319 East Gregory Street. The house belonged to Mr. Charles W. Gray who was a special agent for the Equitable Life Assurance Company. She was buried in a common unmarked grave in St. Michael’s.

At this point the medical staff of Pensacola was on the verge of collapse from the long exhaustive hours and the constant stream of victims. But as the early frost of fall continued to hold off the inhabitants of Ferry Pass were now in a quandary. Alfred Majors and some of the other men of the Ferry Pass community met to decide what direction they should go. Many of them needed to go into town to conduct business and obtain supplies but they were too afraid of the yellow jack. But to date there were hardly any victims that lived above Cervantes Street, which gave them confidence that Ferry Pass might yet be spared. So, one of the Parazine’s were chosen to take a wagon north to Molino and load up with badly needed supplies for their neighbors and return as soon as possible. In this way no one would have to go south into Pensacola and risk becoming infected and possibly bringing it back to Ferry Pass. Since the crops had already been harvested prior to the epidemic most of the farmers were in good shape once they obtained the few essentials that each of the families needed.

In the meantime, the death toll grew higher and higher. On October 25th five more took the path to the pale nations. First was a 38-year old housewife who died at her home at 231 West Zarragosa Street. Mrs. Lizzie Agnes White shared the home with her husband Paul, a bartender for Joseph Arbona’s place at 145 East Zarragosa Street. Her husband had her buried in St. Michael’s. Her husband’s employer, Joseph Augustus Arbona, (Photo #23) was the son of Eugenio Arbona who had immigrated to Pensacola in 1873 via Georgia and Spain and seven years later became the owner of his own bar called the “Gulf Saloon” (Photo #24) on East Zaragossa Street. His wife Fannie Trice gave him five children of which Joseph was the third. The younger Joseph took over the saloon when his father passed away on July 15, 1890 while visiting his family in Spain. Joseph would eventually marry Margaret Lena Pfeiffer and pass on himself on August 16, 1951.

Another was a 32-year old man by the name of Frank C. West who was a carpenter that died in his bed at his home at the corner of Main and Alcaniz Street. He joined the others in the huge common grave at St. John’s. Next came 41-year old Mrs. Euella B. Stearns, wife of W. A. Stearns. She died at her home at 313 North Alcaniz Street that she shared with a steamboat captain by the name of Henry Burlison. Then came a 36-year old contractor by the name of G. B. Morasso who died in his home at 217 North Reus Street that he shared with Albert Morasso, a laborer for the Harry Grant DeSilva Company (Photo #25). These were the children of John Morasso who had died previously on April 9, 1901 at the age of 65-years old. G. B. was preceded in death by three of his children; Augustine, who died of cholera on June 1, 1899 at the age of sixteen months old and two infants who died on September 6, 1901 and May 13, 1902 and were buried in St. Johns.

After his brother’s passing, Albert continued his employment at the DeSilva Company that manufactured rough lumber, shingles, doors, sashes, and blinds on East Main Street. The owner of the company was born on July 12, 1863 and would pass away himself at his home at 110 West Gadsden Street on May 1, 1938 after a short illness. The last to die on the worse day of the epidemic thus far was 19-year old Bryan D. Cheetam who passed away at his home on 225 North Devilliers Street and was buried near Morasso in St. John’s.

On the 27th of the month Pensacola’s seventy-fourth victim was added to the grim reaper’s list. Eugene F. Cartledge was a young 19-year old boy from the farming community of Cottondale located to the east of Pensacola. He had come to the big city to make his way in the world by getting a job at the L&N Railroad station in one of their many shops. With money in his pocket he had found a roommate to share the expenses of room and board at one of the local boarding houses at 613 East Salamanca Street. His roommate was a 46-year old bartender by the name of Frank Carle and both men appeared to have the world by the tail until the day Eugene was bitten by an infected mosquito. Five days later Dr. William A. J. Pollock (signature Photo #26) pronounced him dead in his rooming house where he lay among his small group of friends. His body was taken to the undertaker Frank Pou and he was hastily buried far away from his home in St. Johns Cemetery in section #28.

The rising sun of the next day claimed a 40-year old man named Samuel Kingnary who died in St. Anthony’s Hospital and was one of the fishermen that contracted the fever along the Pensacola waterfront and paid the ultimate price. After the 28th there appeared to be a miraculous lull in the number of victims coming into the hospital or being reported to the authorities. Everyone’s hopes were raised to think that there might be a light at the end of this nightmarish tunnel. Even so only one victim succumbed to the fever during the next five days, one of the longest periods without a death experienced since the epidemic began. This death was that of a 45-year old woman named Mrs. Elizabeth Bazier who died at a boarding house at 500 East Chase Street that she shared with a laborer named Barney Johnson. She had only been in Pensacola for two months and had no money of her own nor could Barney afford to bury her on his meager salary. Thus, Barney helped carry her lifeless body down the stairs and onto the wagon where she was taken out of town to the Poor Farm never to be seen again.

However, everyone’s hopes were dashed when on November 2nd a commercial traveler named E. Fowler Thames who lived at 932 East Strong Street died during the night bringing the total to 78 dead out of 485 infected. Later estimates have raised that number of infected citizens to 1,052 and those that perished from the disease as much as 150. But the discrepancy in the number of victims is to be expected given the record keeping procedures of the day during such a major disaster. By November the mosquitoes were starting to die off with the onset of the colder weather but even though the disease-ridden insects may have been down they were certainly not gone.

Five days later, on November 7th Josephine Irene Quina of 406 E. Intendencia was reported as one of the last patients to come down with the symptoms of the dreaded disease. She was the wife of Julian Joseph L. Quina who was a well-known and successful businessman in the area. Ms. Quina would recover and live until 1944 when she died at the age of 60-years old and was buried in St. John’s in section #60.

Josephine Quina recovered from her confrontation with the grim reaper, but he was still not through with his last few rounds from other patients who were still suffering from the complications of the disease.

On November 7th a boy by the name of Michael Quigles died at his home at 216 South Florida Blanca Street where he was living with his brother Matthew Quigles, a barber for Antonio Bisazza at his shop at 513 South Palafox Street. Being of a good Catholic family the only place the family would consider for his burial site was St. Michael’s. Six blocks away another drama was unfolding when Mrs. Florence Bonar took a turn for the worse. She was eight and a half months pregnant when she came down with the fever. Her husband Frederick was the British vice consul who had already died on October 10th and now her condition was worsening as well. Finally, on November 12th she gave birth to a stillborn son as yellow jack claim its youngest victim so far. Three days later, on the 15th Florence gave up her spirit as she desperately tried to overcome the demands placed on her body from both the aftermath of childbirth and from the debilitation of the fever.

By the 11th the last patients were being discharged and the epidemic was finally declared officially over but there were still two more victims to pencil in on the list of death before the banshees would finally fly away for good. One was 38-year old Mary Sandusky who lived with her mother Margaret, the widow of George William Sandusky, at 330 East Gregory Street. Living with them was her sister Lizzie and their brother Cochran who was a cashier at the Gulf Machine Company (Photo #27). Two more of her brothers had moved in with them to help with the living expenses. These were Emily McKay and John P. Sandusky, the latter of which was employed as a cashier for the Union Naval Stores Company. When Mary was inflicted with the fever the family moved her out of town to the community of Goulding located about where Palafox and Texar Street are located today. However, the move proved futile and Mary died on November 16th and was buried in St. John’s. At the end of the line for the journey into the pale nations was a 26-year old carpenter named Gilbert A. Hoden who lived at 821 North 7th Avenue with Mrs. Addie A. Butler, the widow of Francis M. Butler. He was buried in St. John’s, the last known victim of the great Pensacola Yellow Fever epidemic of 1905.

Sometime after the epidemic was finally over the city health officer Obed Pryor left his position and passed into obscurity. Before he became a health officer he was working as a grocer at 108 East Government Street in 1895 and boarded at a rooming house at 414 East Intendencia Street. When he left public service, he went to work at a furniture store in 1916 and died several years later on June 1, 1924 at the age of 62-years old. He was buried near many of the epidemic victims in St. Johns Cemetery in section #47.

The city physician Dr. Juriah Harris Pierpont continued his medical practice in Pensacola for decades afterwards. He was born in Savannah, Georgia on February 25, 1864 to the union of James Lord Pierpont and his second wife Eliza Jane Purse. From a historical standpoint his father had been the composer of the Christmas melody “Jingle Bells” while his son had chosen the less melodious field of medicine. Juriah began his medical training at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond, graduating in March of 1888 at which time he began his internship at the Richmond City Almshouse Hospital. Because of his mother's illness, he moved to Winter Haven and then on to Pensacola on October 25, 1888. He soon fell in love with a young lady by the name of Lucy Penelope Warren and they were wed on August 21, 1894. She was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Fuller Warren where her father was the founder and president of the Warren Fish Company. His company was a major supplier of red snapper and grouper all over the United States. When Dr. Pierpont began his practice, he noted that Pensacola lacked any kind of medical organizations so in 1888 the Pensacola Medical Society was formed. In 1894, he was appointed assistant surgeon for the Pensacola division of the L&N railroad, a position he retained until 1935. On October 1, 1940, he retired from active practice and died at the age of 79-years old on May 23, 1943 amid World War II and was buried at St. John's Cemetery in section #19.

Photo #1 Store of J. George White, 44 East Gregory Street

Photo #2 Dr. Juriah Harris Pierpont

lives at 18 West Larua Street

Photo #3 Plaza Hotel, 102 East Government Street

Photo #4 George Shuttleworth Brent

lives 108 East Romana Street

Photo #5 Escambia Hotel, 211 North Palafox St., Palafox and Wright Street

Photo #6 St. Antony's Hospital, 104 West Garden Street

Photo #7 Judge Boykin Jones, 119 West Strong Street

Photo #8 Quarantine Enforcement

Photo #9 Dr. William C. Dewberry AD

Photo #10 Clutter Music House AD, 114 South Palafox Street

Photo #11 Avery Hardware Company AD, 2 South Palafox Street

Photo #12 Lives at 19 West Chase Street

Photo #13

Photo #14 Eradication of the mosquito

Photo #15 Dr. William A. J. Pollock

lives at 516 North Palafox Street

Photo #16 Graves of three sailors who fell victim

Photo #17 Captain Lars Andersen

Photo #18 Early morning transportation of the dead victims

Photo #19 French Piano Company AD, 14 West Garden Street

Photo #20 Bosso Yellow Fever Medicine AD, 14 East Government Street

Photo #21 Thomas Watson & Company AD, 1 South Palafox Street

Photo #22 Passing of Angelo Coropos, lives and works at 201 West Intendencia Street

Photo #23 Joseph Augustus Arbona, lived at 221 East Government

Street and worked at saloon at 144 East Intendencia Street

Photo #24 Gulf Saloon AD, 144 East Intendencia Street

Photo #25 Harry Grant DeSilva Company AD, 110 West Garden Street

Photo #26 Signature of Dr. William A. J. Pollock

Photo #27 Gulf Machine Works AD, 817 South Palafox Street